I’m so excited to get into it today, so let’s waste no time in beginning this week’s:

Last week, I recorded our usual podcast at the usual time, this episode featuring Async.Art co-founder, Conlan Rios, alongside Colborn and I. I set to editing the thing on Thursday, and released it, as usual, Friday morning.

Upon opening my computer again after a July 4th spent mostly away-from-my-keyboard, I encountered the following reply to our initial podcast post, which I had missed as it was posted:

Besides wanting to extend my gratitude to Metageist for his kind words, I also wanted to take a moment to express how that post made me feel. Transparently, it made me feel quite a lot. I, laying lengthways on the hand-me-down couch in my living room, stared at this photo of a small toy car for some time awash in what I can only describe as teary euphoria.

No, not euphoria. More like relief. Like a weary warrior who can momentarily set down his greatsword, the battle temporarily overcome, the morning quiet, the labor justified.

This feeling doesn’t come frequently, mind you. It doesn’t appear alongside every kind word we receive. I suspect most creatives have some kind of unfortunate and ingrained compliment filter; only some small, misshapen things slip through. But it appeared alongside Metageist’s words: the recognition of another which spawned a recognition of myself.

I ran to my computer and started jotting down notes, because I understood all at once what I’d be writing my newsletter about this week.

It’s not really a confession, but more of a realization, not the first time I’ve come to it, but each time it shines with an unfamiliar luster: I really love writing about crypto art. And, on top of that, I think this great gift of creativity so common in crypto art is worthy of at least a day’s celebration.

You know, back in my darker days, when my writing wasn’t read by anybody ever, I had this kind of mantra I’d repeat to myself, something to validate the toil. It was, more or less, “If only one single person reads something I write, and if it makes them feel or think anything at all, then I will have had a calculable effect on the world with my work.” It was the lowest-possible bar I could set for myself, but I was hellbent on imbuing that bar with meaning all the same. Just one person, just one life in some small way even briefly contacted, that is all it would take, that’s all I would need, that’s all I could ever ask for, it alone would make the entire grand, constant, deafening process of doing-improving-doing-improving-revising-improving-doing-finalizing-publishing worthwhile.

This was a lesson I learned somewhat in my other life, one I hint at often but rarely discuss in detail.

As some of you may know, I worked for over half-a-decade in the restaurant industry. I was doing various things, delivering pizzas, bussing tables, serving food, tending bar, managing the floor, and my very last industry position was as a server in a high-end, only-somewhat-pretentious French restaurant in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The restaurant was consistently placed in the Greater Boston Metropolitan Area’s restaurant upper echelon. Hell, Boston Magazine named us the Best Restaurant in Boston in 2019.

I worked my way up the ranks there, I saw the comings and goings of managers, bartenders, plenty of prospective servers, a host of cooks, I became a kind of sommelier, I became a consummate professional in that place, all while a single thing remained constant:

The chef.

The restaurant’s chef and owner was a man of elite culinary talent. He spearheaded the creation, growth, and decade-long sustainment of a cuisine many came from far-and-wide to sample. The man was a genius, one of those artisans who had certainly forgotten more about his craft than most chefs would know in their lives. But as respected as he was, the chef was also widely revile. It was simple really:

He was a fucking bastard.

This isn’t news. The dude was well-aware of his reputation. It didn’t matter that his restaurant served a higher-end clientele. It didn’t matter that he worked in an open kitchen where he and his kitchen staff were preeminently visible. It didn’t matter that his hostile work environment was the stuff of gossiped legend throughout Boston’s dining culture. It didn’t matter that his conduct routinely scared away all but the most iron-hearted new hires. The man was an animal.

He shouted. He shrieked. He screamed obscenities. He threw things. He directed his ire at the nearest possible source, whomever they were. His rage was a matchstick and every single god-damn thing in the restaurant could be its spark. I quickly lost count of the insults he hurled at me from across the pass. It was a daily occurrence, worse when it was busy, and it was often busy. I would sneak into the bathroom for a moment to suck on my Juul, and I’d still hear his ambient outbursts through three walls and down a hallway. In his eyes, we were all slow, pathetic, terrible at our jobs, unknowledgeable, annoying miscreants, over-questioning and under-performing, we couldn’t sell, we couldn’t memorize the menu, and he regularly invoked the memories of service staff of yesteryear in order to ridicule how far his restaurant’s hiring had fallen.

When you’re in an environment like that day after day, you have basically two options. You can wilt and falter and quit, which, believe me, many did. Or you can cease to derive value from the places you derived it before. Our Chef —embodiment of the restaurant itself— was a tyrant, and no value could be found there while maintaining sanity.

The only place to derive value, then, was from the guests. Every decision, every sacrifice at our Chef’s altar, it was all to provide pleasure for the guests who occupied tables. “Do it for the guests. Do it for the guests.” I etched that shit into my soul and kept it front-of-mind during each and every service. It was my compass through years in that place, and I have to imagine that a similar realization, earned through an impossible array of varying means, did the same for many who held my position, in that restaurant and in others around the world.

This life, this writing about crypto art life, is markedly different, of course. Those who I work for today are angels: encouraging, admiring, kind, open, and inspiring.

But the crypto art world itself is a tyrant. It is our chef. It is harsh and cruel and mocking. It celebrates pathetic people who do insufferable things, and it denies the efforts of the hard-working, the brilliant, the thoughtful. I do not describe myself with these adjectives, but I certainly describe so many of the artists I admire, the thinkers and developers, the critical minds, the earnest collectors, the curators, the event organizers, the interns I am blessed to encounter in my days here.

You all, whom I write for, as we bulwark ourselves together against crypto art’s never-ending onslaught.

We all know that this crypto art world is a fearful sort. It bullies us, and it puts us down. It taunts us, cackles, chortling about our unworthiness, our talentlessness, and it is specially-equipped to validate our inadequacy.

“If you were good, your art would sell.”

“If you were good, you would have more followers.”

“If you were good, more people would read your writing.”

It is perfectly-designed to destroy us, in whichever ways our individual weaknesses allow it.

Come on, I’m no different than anyone. I can’t help but dwell on readership statistics. I can’t help but notice how many people tuned in to the podcast each week. Doesn’t matter the number, the kind words, the reputation of our guests, crypto art is there to taunt me.

“I thought you were good at this,” it whispers, “but I guess we were both wrong.”

And I look down at my soft, un-calloused hands (a writer’s hands don’t callous, rarely scab, never scar). And I wonder if you can even call what I do labor, if I’m earning my keep, if I’m worthy.

But then I see Metageist’s post, and the others like it, and my whole forgotten history crashes through the ceiling. I remember what I would say to myself in the restaurant days: “If I can make one person smile, I will have accomplished something tremendous.” And sure, back then I could look down at bleeding, burnt, strained hands for confirmation, but anyone who thinks what we do here (be it code, make art, write, curate) isn’t hard labor, they’re ignorant.

This is our labor, our true labor. To make some impact, no matter how small, momentary, or limited. No matter what creativity we bring to the world, if it can rustle a single soul, it will have been a wild success. It will have had a quantifiable effect on human history, in some small way. We make that our mission because we must.

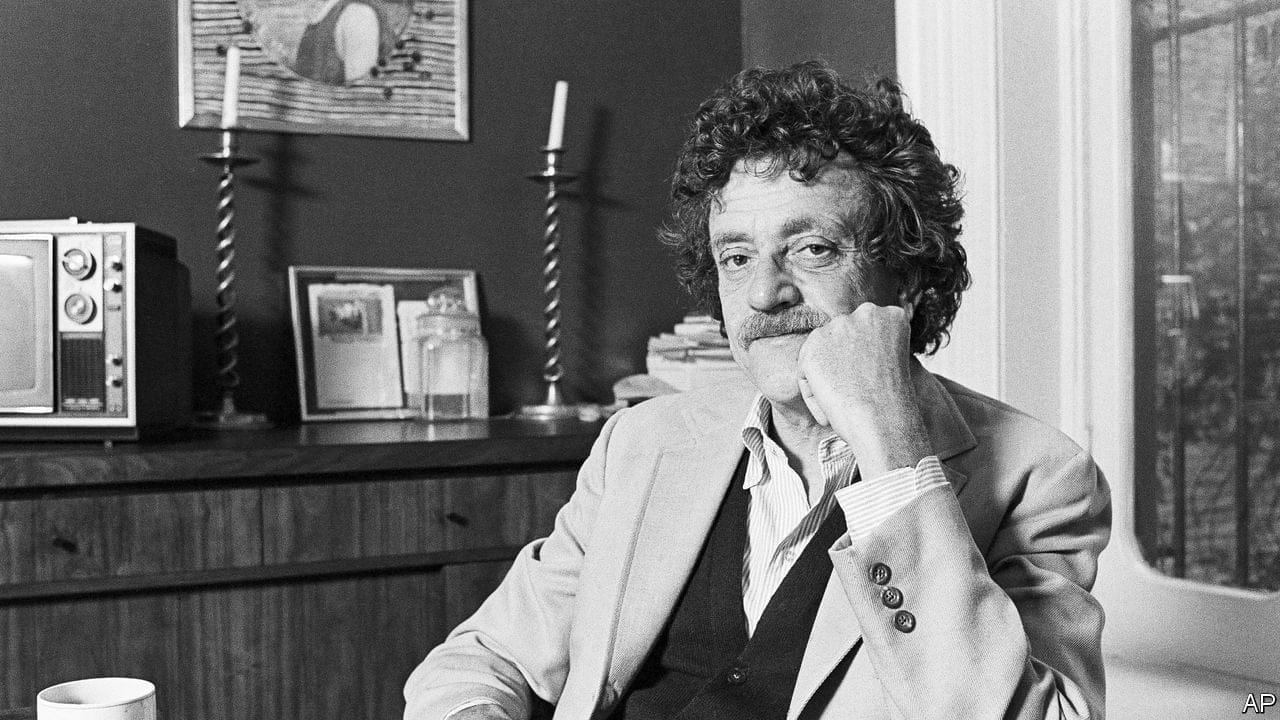

I invoke the inimitable Kurt Vonnegut, who once said:

“…go into the arts. I'm not kidding. The arts are not a way to make a living. They are a very human way of making life more bearable. Practicing an art, no matter how well or badly, is a way to make your soul grow, for heaven's sake. Sing in the shower. Dance to the radio. Tell stories. Write a poem to a friend, even a lousy poem. Do it as well as you possible can. You will get an enormous reward. You will have created something.”

And I love writing about crypto art because it is not only a method by which I can remind myself how and on what to correctly focus, but because I am routinely walking astride those who are reminding themselves, and each other, of the same thing. We engage in these cycles of damnation and revival again and again with each bull or bear market, and we do so together.

The best moments in the restaurant came after service, the staff huddled together in the basement, ripping vapes, cursing the chef, weary and battle-tested as a team. It is no different in crypto art. This space is at its best when we are complimenting each others’ artistic brilliance. And we do, often. It is at its warmest when we are honest, and we are so often honest. We desperately need good people around us, and we find them, they come to us, we are attracted to each other, and it makes the work palatable, no, more than that, it makes it sweet.

Sometimes, that is…when we can remember.

Call me saccharine, call me unrealistic, call me quixotic, call me any number of four-letter words, have at it. The cynical artist has lost the battle. The cynical artist is the walking dead.

I am lucky enough to sit within a community that may succumb to suffering, may engage in misery, but only very rarely gives in to cynicism. If crypto art were a cynical place, we would not sing each others’ praises. We would not openly admire our allies. We would not send out for public consumption the fact that we listened to a podcast, that we liked it, that we were on a river, that we found a small toy car on the way.

Writing about crypto art let’s me again and again become aware of that fact. A fact so beautiful, and so enthralling, and it fills me with love, appreciation, and gratitude, again and again. No matter how many times I forget, it reminds me.

If you are reading this sentence right here, I will have accomplished all I ever set out to do. You will have had your own calculable effect on this life, mine, right here in front of you.

And that…I love that. I truly, truly do.

-Your friendly neighborhood art writer,