MOCA Confessional: I Never Collect Artwork (Why That Is, and Why It's Hard...)

In so many words...

Yep, it’s that time of the week again, time for another big, fat, wet, walloping edition of:

You know what that means: I get to make an ass of myself, again, over the course of a few-hundred (thousand?) words. And make no mistake, I will make an ass of myself. How can I be so certain?

Because part of today’s essay includes being a bad friend.

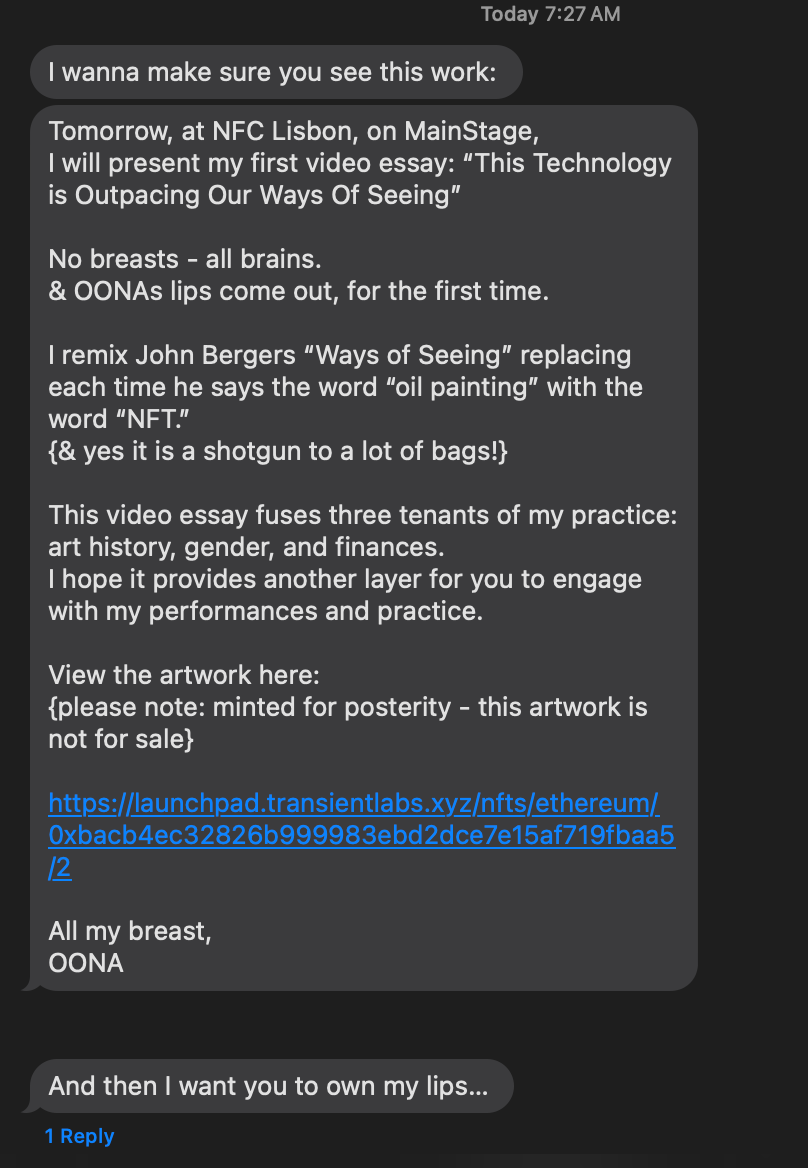

Let’s back up a bit, to Tuesday morning, when I woke to a text from the debonaire performance artist (and true-blue friend to your esteemed writer, here), OONA:

If it weren’t incredibly apparent by the essay I’ve written about her, the THREE MOCA LIVE podcast episodes she’s been on, or the effusive admiration I spew about her to anyone who asks, I’m a massive fan of OONA’s artistry.

And this work is another sterling step upwards in the great ascendency of her career: bold, creative, performative, on-brand, sardonic, take-no-prisoners. It’s called This Technology Is Outpacing Our Ways of Seeing, and it’s beyond worth six minutes of your time.

I could spend this entire newsletter singing OONA’s praises, but let’s let the work speak for itself; I’ll use it only as a springboard.

Because that last text of OONA’s (“And then I want you to own my lips…”) referenced a purchasable artwork (the above video was minted only for posterity and is not for sale) called From My Lips to Yours, which is the opening title card to the video referenced above, with OONA’s grapefruit-red lips pursed in the center of a frame around which scrolls —in Matrix-like font and color-scheme— the title of the video, “This Technology is Outpacing Our Ways of Seeing.”

From My Lips to Yours is reasonably-priced at .024ETH. It is both itself a pristine work of art and exists within the context of another work which I found well-executed, creatively-designed, and aesthetically-jazzed. Not only is it within my price-range, but minting an edition would show support for a brilliant creative and good friend.

And so, my friends, we come to the part of today’s newsletter where I —as promised— make an ass out of myself.

Because I’m probably not going to mint this artwork. I’m going to leave the tab open on my browser, I’m going to watch the ticker slowly die down, I’m going to admonish myself for treating the requisite purchase-and-transfer of .024 Ethereum as a too-difficult task, and I’m inevitably (probably) going to let my friend’s wonderful artwork go unminted.

Confession time: I don’t like to collect crypto art.

“But Max,” I hear you say, “It’s so easy, and it’s not like you’re short of the requisite funds.”

Which is true!

“But Max,” you continue, “This is a friend of yours, and your support will go so far, will it not?”

You’re absolutely correct.

“But Max,” please stop, I can’t take it anymore, “You love crypto art! And you clearly care a great deal about artists! And I’m going to go ahead and assume that the technological concerns about holding/stewarding crypto art do not factor much into your thought process here.”

Yes, yes, and also yes.

“So why then? Why wouldn’t you collect a work like this?”

I would like to spend the breadth of today’s newsletter trying to answer that question.

You know, mine is an interesting position in crypto art. It is no new conjecture to claim that this is a space —like nearly all creative spaces— that thrives best when money is flowing rapidly and massively. When art sales are frequent, money flows into the hands of artists, and artists are always the best supporters of other artists. That was true when Picasso collected Cezanne, when Matisse collected Picasso, and it is true today. This is really the only reliable way we have for supporting emerging artists and styles, and if you know another one, please let me know. We can detest the profiteering nature of both the traditional and crypto art worlds, but funds do tend into the hands of those who will champion less well-known artists, fringe artistic brilliance, the avant-garde, all the things that artists love, once were, or instinctively recognize.

We can pretend that the goal of most artworks is not to accrue financial reward, but that’s what motivates all of this public creativity. It’s why musicians release music, why writers publish writing, why crypto artists mint artwork. Make art, sell art, and receive the ensuing freedom to do nothing but create art as one’s primary income stream.

Upon my writerly perch, I am somehow both personally invested in crypto art’s success and almost entirely financially uninvested in it. I do own some artwork, but these were generally things I purchased in my earlier days, when I was a bit more cash-flush, things I bought —let the shaming come— for their investment potential (which always carries an aesthetic component, to be fair), or pieces I felt would help me become further ingrained in a crypto art world I was trying to demonstrate my commitment to. But over time, my desire to collect has disappeared almost entirely.

Part of that comes down to simple finances. I live in New York City, the single most expensive place to live in the world, and I like to travel, and I like to buy rare sneakers, and I like to go out to dinner with my friends, and I like expensive coffee, and I take a $15 train both ways whenever I want to go see my parents, and the costs of life quickly add-up. Crypto is generally posited as a place where one can get rich quickly, but I’ve never gotten rich at all. I’ve been lucky enough to eke out a fairly-fantastic living for an art writer, and I get by okay, and when I have money to burn, it’s generally on things that exist in the real world.

This is probably not a very unique space to occupy, yet it is also one that brings with it a not insignificant amount of shame. After all, these are my people. Crypto art is my world. To not support it financially, to prioritize all these other things instead, that does at times feel like a betrayal not only of the crypto art world, but of its many citizens, people whom I really do care about and wish success for and want to watch rise.

The other part of my collecting-less ethos is more difficult to enunciate, but I suppose it comes down to this: I get no more joy from collecting an artwork than I do from looking at it, and certainly less joy than I get writing about it. If the traditional reason for collecting artwork was to have that thing on daily view in your life, then that is no longer a problem. I can see, save, print any artwork I see on-demand. We can deride the “Right-Click-Save-As Guy” for their naivety, but that’s a real thing. I once fell in love with the work Ethereal Monastery by Diogo Sampaio, so I saved the image and made it the background on my phone. And so, no, I did not own it, I could not sell it, but still, it was with me.

And that means something.

But also, and this is just as important, there is a spiritually-enriching consequence to writing about an artwork. Spending that much time with the thing, thinking about it for so long, is like doing a dance it, not making my mark on it per se, but coming close to it, smelling its hair, feeling its fingernails in my palm, a sweet and sensual moment that brings me far more fulfillment than simply holding the thing in my wallet.

I visit the oh-so-detailed world by my chronicling of it. I form relationships with things —characters, artworks, people— by wiling ample time away with them upon a blank page. While I despise haughty characterizations of writing, it does have a unique capacity among the arts to bring you near to your subjects. Sometimes that translates into actual, quantifiable relationships. I would be remiss if I thought that my friendships with OONA, Matt Kane, or Anne Spalter did not, in some part, arise because of my writing on them. But most of the time, it is a very internal kind of relationship that emerges, just me and an unwitting subject; people are often unwitting, artwork always is. And when you have the capacity and encouragement to form those kinds of relationships, so nuanced and personal and incommunicable, little else will do.

And that means collection lacks any real luster. I do want to support my friends. I do want to add my own little bit of incentive to the creation of wonderful art. But collecting an artwork feels sudden and meaningless, and all so that the work can exist in a little bucket beside me. I can and will revisit the things in that bucket; I can exchange a wink and a nod with the artworks I’ve collected, but I can’t know them the way I know the things I write about.

And once you know that writerly relationship, you crave it. Unfortunately, nothing else will do.

I thus occupy an odd and sad kind of limbo in an art movement. We can all pretend to the contrary, but the truth is that artists do, should, and must prioritize collectors above all other people. I mean, collectors are the artist’s lifeblood, the thing standing in the way between them and the life they seek. As a writer, I can bolster the artist’s self-belief, and I can offer encouragement of a kind, and I can perhaps even convince collectors to collect an artist’s work or increase their conviction in a purchase, but that makes me little more than lubricant. Don’t pity me! Lubricant is often necessary! And those who love lube love it a lot. There are very few situations that lubricant makes worse. But it is an accessory to the thing. It assists an outside relationship, in this case, that between artist and collector.

This is a highly exaggerated feature of crypto art, with art collection being so public. Collection is incorporated into someone’s public image. It leads to notoriety, admiration, and opportunity. You get no kudos for merely admiring artwork. You get stronger kudos if you write about or curate artwork, to be sure. But all three pale in comparison to the kudos you get as a collector.

I imagine this is why many art critics come across, to me, as bitter or even cruel. They cannot penetrate exist the world they nevertheless live in, which only becomes more glaringly apparent the higher in that continuum you elevate, with more successful artists, more expectant collectors, even less of a chance at participation.

But this does not change the paradigm itself, that the writer has an avenue towards closeness with artwork that is probably only exceeded by those who created it, that in comparison makes collection feels pale. This dichotomy creates a difficult-to-articulate and paradoxical paradigm of closeness and distance. Unsurpassed closeness to the thing, and by consequence of that relationship, a deep chasm between we and what we purport to support.

Which is all a long way of saying that when I am confronted with an opportunity to collect an artwork, no matter its context, I ask, “Why?” What do I receive from this collecting other than the sense that I am doing a good deed? How is my life singularly enriched by the process of collecting itself?

At this point, I do not have a positive answer to those questions.

Now, I do not want you to think that I am in any way dismissing or diminishing the power of collecting. For those who derive much from it, it is an exercise of cultivating muchness. It is a relationship manifested, and a show of care, and a promise of protection. It is the single most important thing a non-artist can do in an art movement.

But I can’t bring myself to it. I can’t convince myself of its worth. And I hope that this will not damage my relationships to and within crypto art, but it must, it has to!

All of which is to say: OONA, if you’re reading this, I won’t be collecting your marvelous artwork.

I hope you understand, and I will not be angry if you hold it against me.

-Your friendly neighborhood Art Writer,

Max